Use Haschicorp Vault, or Mozilla SOPS?

Summary

Following a recent post about SOPS and Docker, I thought to write about Vault and Docker, doing a very similar task of secret management.

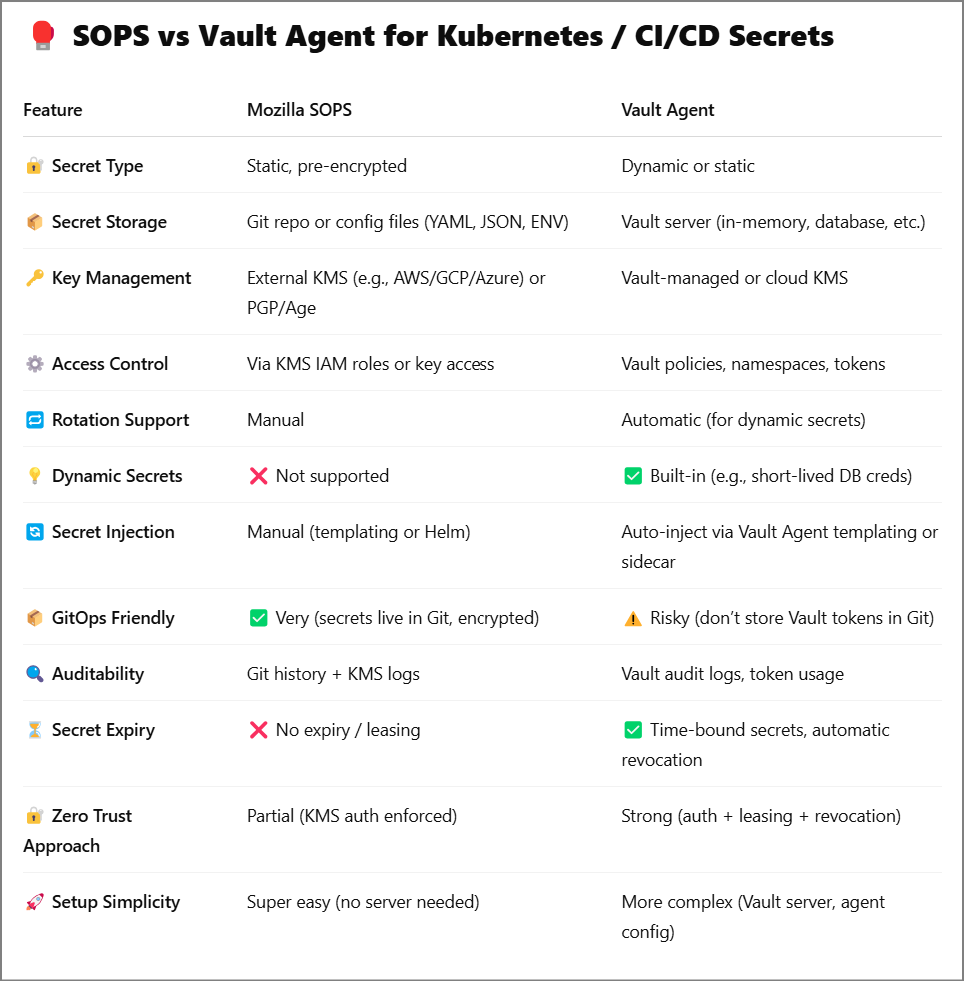

One difference with the two tools: SOPS is a tool for encrypting/decrypting files, as well as editing them. Vault Agent is a tool for retrieving secrets from Vault. Both can provide secrets and output them in various formats (output a file, an environment variable, etc), but:

- Vault Agent is a tool to simplify integration with Vault, i.e., retrieving secrets. It does not take input of encrypted data and output decrypted data like SOPS does 1.

- SOPS is a tool for interacting with a KMS or decryption keys locally. I.e., you provide it encrypted data, and it provides you back decrypted data, or vice versa.

Vault Agent vs SOPS

I’ll copy this text from Google’s AI-assisted response:

Vault Agent and SOPS are both tools for managing secrets, but they differ in their approach and scope. Vault Agent is a component of HashiCorp Vault, acting as a proxy and simplifying application integration with Vault, while SOPS is a standalone CLI tool for encrypting and decrypting files, supporting various encryption backends and formats.

The way I like to think about them is:

- Vault Agent is a proxy for pulling secrets2. You get to see the secret.

- SOPS is a bit like a proxy for a KMS3. You never get to see the decryption key with a KMS.

Why is this difference important?

This article articulates it well by calling out something important: you can’t revoke decryption keys, the way you can revoke certificates. Committing encrypted secrets is dangerous if you have any access to the encryption keys, because eventually someone is going to leak that key. Then you’ll never be able to erase the git history4 and your secrets will be exposed.

If you’re using Vault to encrypt/decrypt with a key that’s stored in Vault, it’s still dangerous to commit encrypted secrets because, again, if encrypted data is commited in git history and the key is later exposed, rotating that key won’t help.

Alternatively, if you’re using SOPS, the article argues that committing encrypted secrets to git is much safer. Because SOPS uses a KMS, you’ll never get to see the decryption key and the chance of leaking that key is “near zero”. Sure, SOPS requires access to the KMS and that’s based on credentials (AWS or Azure identity, for example), but rotating those creds is very cheap and easy.

Secret Rotation

I’ve started to think about secret rotation in a more structured way recently. We always need to be able to rotate secrets, but I also think about categories of secrets. Which secrets are most important to be able to rotate quickly? What are the implications when we take a layered approach? Currently I am thinking of 4 categories:

- Secrets used for access to something. These are secrets like passwords, mTLS cert/key pairs, and API keys that we obviously need to keep out of code. We should be good at rotating these but often we are not. For example, to update your app server may be a manual import of a certificate and a service restart. That costs effort, downtime, and coordination.

- Secrets for pulling these secrets. These are things like AWS IAM creds or TLS certs used to authenticate to a secret manager, or to a KMS. These should be very easily rotated. There is not a good reason for them to be long-lived, since these services are not legacy themselves and rotation is trivial.

- Decryption keys. You cannot revoke a decryption key. If it’s leaked, you need to rotate it, but anything that was encrypted needs to be re-encrypted. And that encrypted data is now potentially exposed, so you need to rotate any secrets in that encrypted data, too. Hopefully that encrypted data wasn’t the actually valuable thing, like your recipe for Coca-Cola. This is why a KMS is helpful: I don’t want to hold a decryption key.

- KMS keys. There’s an argument against rotating these. I’m not expert enough to argue strongly for or against.

To rotate, or not to rotate?

KMS usage helps because you have a layered approach with a Data Encryption Key (DEK) and a Key Encryption Key (KEK). I don’t mind holding an encrypted DEK. You could argue against rotating KEK’s if you trust your KMS (HSM-backed, access controlled, auditable logs). But that’s a topic I’m no expert in, and also something you can generate a fuller argument on using AI, so I won’t blog about it.

My experience in corporations

The more I think about this at real-world businesses in which I’ve worked, the first kind of secret rotation is pretty hard to consistently get right. Sure, great DevOps folks practice great secret management, but most organizations have some apps that are legacy and include imperfect practices like manual processes to update passwords in systems. That makes a layered approach very important.

I’d be happy to use Vault Agent and Vault if all secrets could be managed extremely dynamically, and the management of the Vault itself could be considered extremely secure. It sounds like cloud KMS-backed Vault is maybe the way to go.

Handy advice from ChatGPT

I can’t take credit for this, but I thought it was nice:

Conclusion

I admit this post is nothing ground-breaking. I started out planning to post about how to use Vault Agent with F5’s App Study Tool running in Docker, but ended up reading about SOPS vs Vault Agent and wanted mental clarity on encryption keys vs secrets.

I suppose I’ll conclude by saying I have a new appreciation for cloud-based KMS services when I consider the potential of leaking a decryption key, vs leaking a secret. One can be rotated so the previous value is made useless, the other cannot. For this reason, I think for my next large project, I’ll start by using Vault & Vault Agent with a backing KMS and strict automation for rotation of identity creds.

-

Actually, Vault Transit is a feature that allows this, but SOPS has more features and is a superior tool if this is the only function being used. ↩

-

I think Vault Agent can also work with a cloud KMS, so here I’m really talking about using Vault Agent as a proxy for secret mgmt in Vault server, only. ↩

-

SOPS can also work with keys that are local, like PGP keys in a local keyring, but this article assumes we’ll use SOPS to interact with a cloud-hosted KMS. ↩

-

You could try to erase git history but if the repo is public, it’s already been copied and exposed. ↩