Migrating F5 between sites using stretched VLANs

Background

Recently I was asked the following question by a customer:

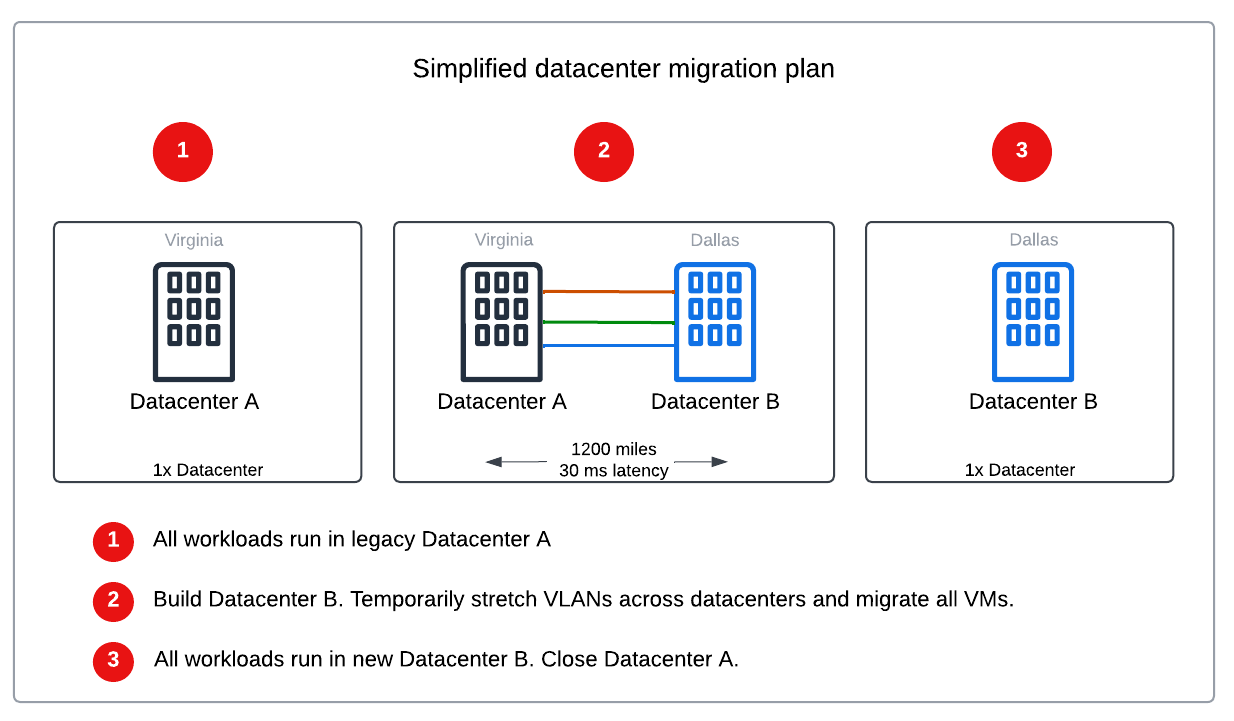

I have 2 physical datacenters. Datacenter A is a legacy datacenter and almost all workloads run here, and Datacenter B is a new location with almost no workloads deployed. I must migrate quickly out of location A into B, in order to close location A.

Using NSX-T, I have “stretched” VLAN’s between sites, meaning that a single VLAN and CIDR block is available to VM’s in either datacenter. I have 2x F5 BIG-IP devices configured in an HA pair (Active/Standby) in location A, but none yet in B.

I have thousands of Virtual Servers configured on my BIG-IP devices, and many thousands of VM’s configured as pool members, all running in location A. I can migrate workloads by replicating VM’s across datacenters, leaving their IP addresses unchanged after migration to location B.

What are my options for migrating the BIG-IP devices to location B? I’d like to maintain High Availability within each datacenter, minimize any traffic between the sites, and minimize operational difficulties.

Let’s take a look at these requirements and review potential solutions.

Defining our migration

Firstly, let’s define our existing environment and challenges in a little more detail.

What is a stretched VLAN?

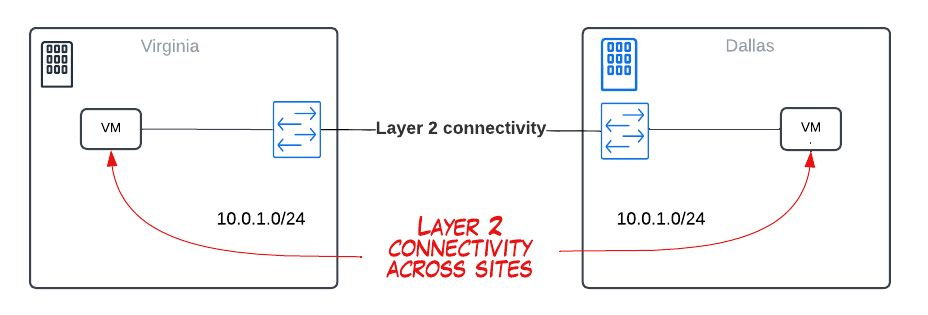

“Stretched VLAN” is a shorthand phrase for the practice of extending Layer 3 networks across physical sites. This is useful in situations like VM migration across data centers without needing to change the VM’s network configuration.

If datacenters are within a few miles of each other, direct Layer 2 connectivity may be possible.

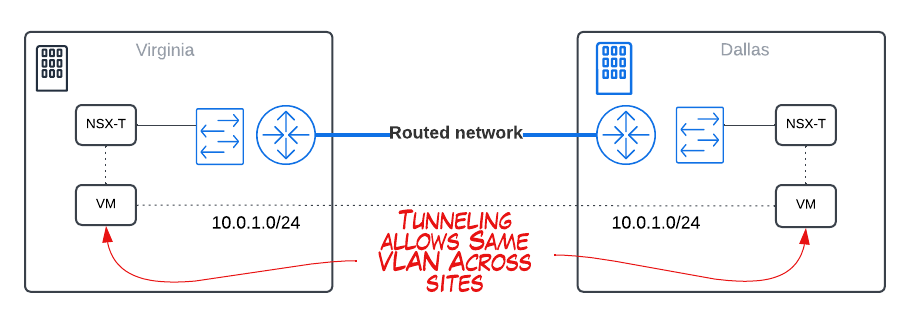

A more commonly preferred approach is tunneling Layer 2 networks across routed (Layer 3) networks. This allows for more control over networking and relieves some constraints of direct L2 connections.

The primary technology used to stretch a VLAN across physical data centers is VxLAN, which allows for Layer 2 connectivity extension over a Layer 3 network, effectively creating a virtual overlay network that can span multiple data centers while maintaining logical segmentation within the VLANs. VxLAN is used by VMware’s NSX-T offering, but other technologies also exist, such as L2TPv3 and MPLS.

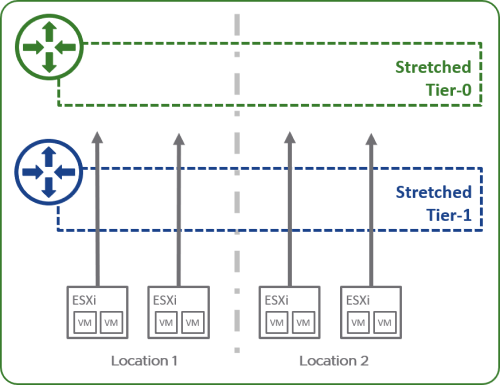

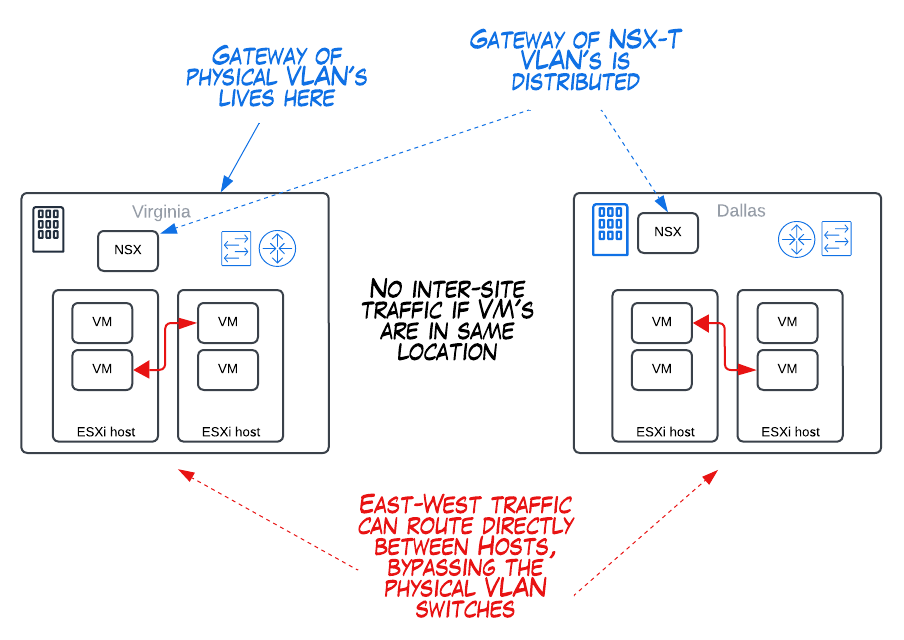

How can NSX-T minimize inter-site traffic?

Because NSX-T can have logically distributed routers, we can define an overlay-backed segment. In an overlay-backed segment, traffic between two VMs on different hosts but attached to the same overlay segment has their layer 2 traffic carried by a tunnel between the hosts.

In practice, this means that traffic between two VM’s in the same segment - even if they are on different VLANs and different ESXi hosts - does not need to traverse the physical network gateway. I.e, if our VLAN’s default gateway of “.1” exists on a physical router in Location A, but traffic is being sent between 2x VM’s on different hosts and VLAN’s in Location B, the traffic does not need to traverse the inter-site link.

This is very powerful. To minimize VM-to-VM traffic crossing the inter-site link, we must configure NSX-T correctly, migrate all VM’s in a given app/workload between data centers at the same time, and also at the same time move any F5 VIPs that process application traffic for that workload.

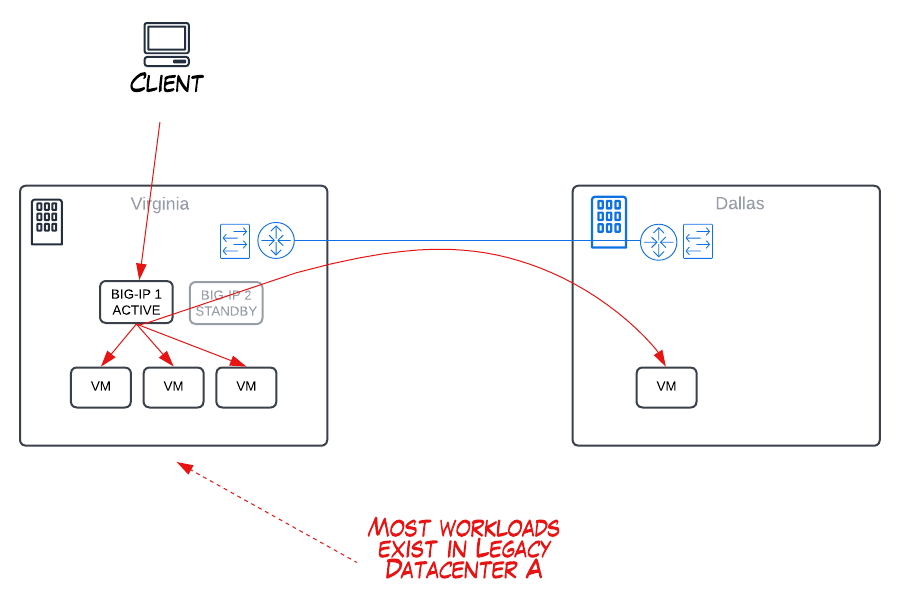

Pre-migration BIG-IP overview

The simplified diagram below shows the customer’s pre-migration environment. The legacy datacenter still hosts almost all workloads, but the plumbing has been laid for migration. Using NSX-T, the VLANs in datacenter A are stretched to datacenter B. Existing BIG-IP’s can reach pool members in Datacenter B. Any VM can be migrated between sites A and B without changing it’s IP address.

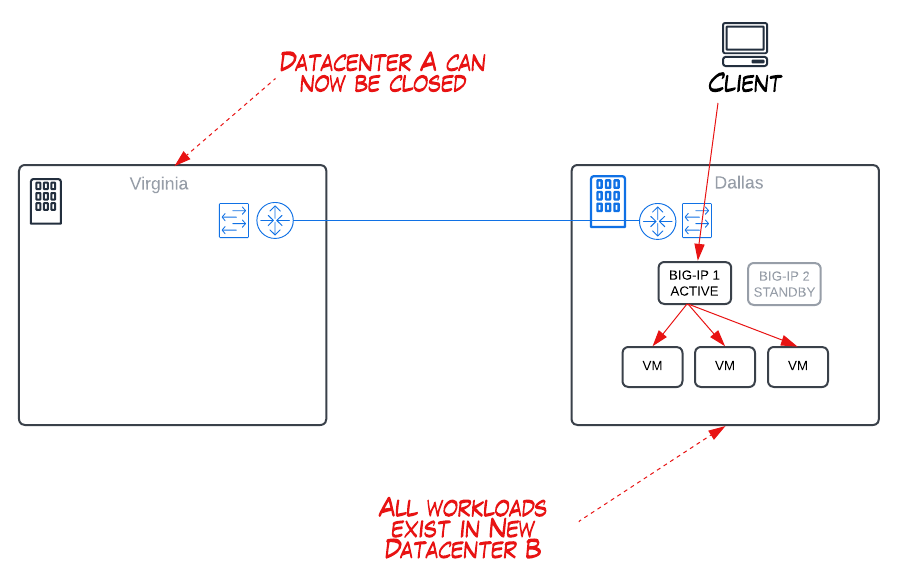

Post-migration BIG-IP end state

The diagram below shows our post-migration goal. Let’s remember our requirements. We want to get here with:

- HA maintained within each datacenter (we’ll have 4 devices for a period of time)

- Minimal inter-site traffic (skip the physical VLAN gateway if possible)

- The easiest method possible (ie, sync configs and do not deploy new config on a disparate BIG-IP cluster)

Migration options

Let’s review a few options for migration.

1. HA pair across physical locations

Given that our end goal is to have all VM workloads and BIG-IP VE’s in location B, we may be tempted to take a shortcut approach: just migrate one BIG-IP VE to site B and run an Active/Standby pair across datacenters. This could work in terms of connectivity, but raises some disadvantages for a production scenario:

- Latency. Only 1 BIG-IP can be Active. Latency will occur for all traffic between the Active BIG-IP and any nodes in the other datacenter.

- HA. Running a single HA pair across sites leaves us without High Availability within either site.

- Hard cutover. A cutover of the Active/Standy roles between site A to site B can be planned, but it’s an “all or nothing” approach in terms of site A or B hosting the Active BIG-IP. There’s no graceful way to keep both VM workloads and the Active BIG-IP in the same site and migrate together.

I have personally managed HA pairs run across two physical datacenters with Layer 2 connectivity. In a scenario with very little latency between sites, or where a migration was not planned, that might be appropriate. However, in this case, the disadvantages listed here make this option less than ideal.

2. Second HA pair of BIG-IP devices in site B

Given that our end goal is to have a single HA pair of devices in site B, we could build a brand new, disparate BIG-IP cluster in site B and migrate Virtual Servers from cluster A to B. After migration, decommission cluster A. This could work but raises unnecessary complications:

- IP conflicts. If we build 2x HA pairs, both on the same VLAN’s, we have the potential for IP conflicts. We must migrate every Virtual Server and Pool by recreating our configuration on cluster B. This means every VIP must change.

- Tediousness. We could alleviate some pain by cleverly replicating the configuration from cluster A on cluster B, but disabling Virtual Addresses until a time of cutover. This would be possible but tedious, and introduce some risk. We could automate the deletion of VIP’s and pools from one device, and creation on another, but this automation is likely to be difficult if the original configuration was not created with automation itself.

- DNS. If IP addresses of VirtualServers do change, we must consider the DNS changes that would be required.

One advantage, however, is that two separate clusters is an architecture that is very easy to understand.

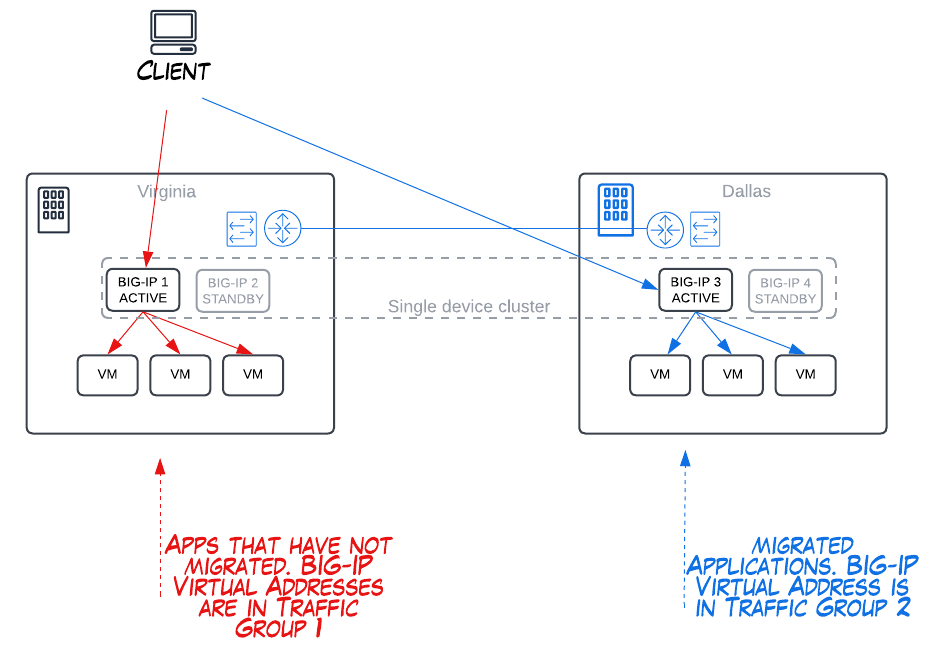

3. Single device cluster with 4x BIG-IPs

This is my preferred approach when latency between sites is non-trivial and we must operate for some time with Active BIG-IPs in both locations.

- We’ll temporarily grow our cluster from 2 devices to 4, with 2 devices in each cluster.

- We’ll introduce an additional Traffic Group.

- Traffic Group 1 (existing TG) will be Active on BIG-IP 1 with BIG-IP 2 as next preferred.

- Traffic Group 2 (new TG) will be Active on BIG-IP 3 with BIG-IP 4 as next preferred.

- Pre-migration, all VIP’s exist in TG 1.

- Migrate workloads components together:

- Migrate related VM’s for workloads to Datacenter B.

- Migrate appropriate VIP’s between TG 1 and TG 2.

- East-West traffic between workload VMs and BIG-IP should all remain within Location B.

- Once all VIP’s are migrated to Traffic Group 2:

- Delete Traffic Group 1

- Remove and decommission BIG-IP’s 1 and 2.

The advantages to his approach are:

- No IP address changes. Virtual Addresses of Virtual Servers do not change.

- Operationally smooth. A TMSH command can move a Virtual Address between Traffic Groups. Workloads can move app-by-app and not in an “all-or-nothing” approach.

- No DNS changes required.

- HA maintained within sites.

Further details when configuring a single, 4-Device Cluster

The basic idea behind this migration architecture is that a given VIP will be advertised via ARP from either Location A or B, depending on the Traffic Group to which the Virtual Address belongs. This allows us to have a single Device Group (easiest because config is synced between all devices) and to use two Traffic Groups.

The Device Group type is still Sync-Failover (and not Sync-Only). In a Sync-Only group, the /Common folder is not synced between member devices, but in our case the existing configuration exists within /Common and so we will need this replicated between all four devices.

Multiple Device Groups within a single Trust Domain, as diagrammed in this example, are not planned in this scenario. Because partitions are mapped to a Device Group, and all of our existing configuration is within a single /Common partition, multiple Device Groups are not appropriate in this case.

Failover is configured individually for each Traffic Group. TG 1 will failover between BIG-IP 1 & 2, and TG 2 will failover between BIG-IP 3 & 4. We often refer to two-node clusters as “Active/Standby” or “Active/Active”. When a cluster has 3+ nodes we often refer to it as “ScaleN” or “Active/Active/Standby”, or similar. For this scenario, we might use the term “Active/Standby/Active/Standby”, since we’ll have 2 Active devices and 4 devices total during our migration.

Further questions for our customer scenario

When do we migrate the default gateway for each of our physical VLANs?

The physical VLAN’s have a gateway - let’s call it “.1” - currently configured on routers on Virginia. This is relevant because some traffic may traverse physical VLAN’s: traffic between VM’s that are actually running in different datacenters because they were not migrated together, traffic from regional sites that are routed by the WAN to Virginia, traffic to physical VM’s that will be migrated separately, etc.

Moving that “.1” from Virginia to Dallas will be once-off move that’s best left to the customer’s network team. Advanced network management technologies can distribute a VLAN and gateway for physical networks, just like our NSX-T example does for VLANs within the virtual environment. But this decision is outside of the recommendation for F5 BIG-IP migration.

What about physical servers in Virginia? How do we handle those?

Physical machines must be re-built in Location 2. Physical VLAN’s can be stretched, just like VLAN’s within the virtual environment. Or, physical machines may reside on VLAN’s that are local to each datacenter. In the case of a stretched physical VLAN, a physical server that is a pool member in BIG-IP could maintain it’s IP address and BIG-IP configuration would not change. If the IP address of a pool member does change, of course the BIG-IP configuration must be updated. This makes the migration of physical servers less automated than VM’s.

In this scenario, the BIG-IP’s themselves are virtual machines. If they were physical appliances on a stretched VLAN, the same approach would apply for BIG-IP migration (single Device Groups with two Traffic Groups).

What about self IP addresses?

This is a potentially important detail. Each BIG-IP will have unique Self IP’s in each VLAN to which it is connected. Let’s walk through this from two perspectives: health monitoring and SNAT.

Health monitoring of pool members will be sourced from the non-floating Self IP that is local to the Active BIG-IP. Health monitoring is not sourced from a floating Self IP, if one exists. By introducing two additional devices we will be adding two IP addresses from which pool members may receive health checks. In our customer’s case, no firewall currently exists between BIG-IP and pool members, so it’s very unlikely that health monitoring from a new IP address will break an application. But it is important to note: if an application is expecting health monitoring to come from one of the two existing BIG-IP Self IP’s only, we may need to update that application.

SNAT, which is extremely common, means connections between BIG-IP and pool members will be sourced from a Self IP. If a floating Self IP exists, SNAT connections will be sourced from this IP address, otherwise they will be sourced from the non-floating address. Floating Self IP’s are assigned to a Traffic Group and will failover between devices accordingly. This means that when a VirtualAddress is updated from Traffic Group 1 to 2, SNAT’d connections will now be sourced from a new IP address. The same potential concern exists for SNAT as with health monitors: if applications or firewalls accept only pre-configured IP addresses, we’ll need to update them.

However with SNAT an administrator might plan ahead with SNAT Lists. SNAT Lists are also assigned to Traffic Groups, and an administrator might create a SNAT List dedicated for an application. This SNAT List could be migrated between Traffic Groups at the same time as a Virtual Address and associated VM workload migration. Be mindful if updating the Traffic Group of a floating self IP or SNAT List: if multiple applications are expecting specific source IPs for health monitors or SNAT’d connections, those applications may need to be migrated together.

Conclusion

A stretched VLAN allows additional options for VM migrations. Careful planning of F5 BIG-IP deployments, using multiple Traffic Groups, will allow for a smooth migration plan. Thanks for reading!