Making K8s shutdowns more graceful

Summary

When pods are removed from Kubernetes services, there is a short time window when requests may still be routed to them by ingress controllers, external load balancers, or other components. This can result in failed requests.

As Kubernetes admins, we can make small changes to make rolling upgrades more graceful for end users. We will focus on the PreStop hook and the terminationGracePeriodSeconds pod setting, and why this is probably more important for external load balancers than ingress controllers.

Covering the basics

Requests are routed to pods

Pods have one or more containers that run applications such as web servers and databases. Pods have IP addresses and in many cases must be reachable by clients outside of the cluster to serve requests. To route traffic to pods we typically point client traffic toward an ingress controller first, which then routes the traffic to the appropriate pod based on Kubernetes objects like Services and Endpoints.

Services and Endpoints

A Service is a group of pods that should be reachable by clients. The Endpoints (plural) of that service is a list of the service’s pods’ IP addresses and ports, but only those that have satisfied their readiness probe. The Kubernetes Endpoints object is separate from a Service object, although for every Service there is an Endpoints.

Readiness probes

It’s important to know about liveness, readiness, and startup probes. Startup and liveness probes help determine if a pod is healthy, and it’s the readiness probe that determines if a pod is ready to receive traffic. If a healthy pod satisfies it’s readiness probe (or doesn’t have a readiness probe configured), it’s IP address and port are added to the Endpoints object for the corresponding service.

How requests reach pods

When requests are sent to new pods in Kubernetes via proxies such as external load balancers or ingress controllers, these proxies must be configured with the IP address of each pod in the exposed service1. Likewise, they must be updated if the pod IP addresses change, such as when deployments are scaled in/out or when Kubernetes replaces a failed pod with a new one. And again, when a pod’s lifecycle is complete - whether the reason is a completed task or a rolling update - the pod’s IP address must be removed from the proxy.

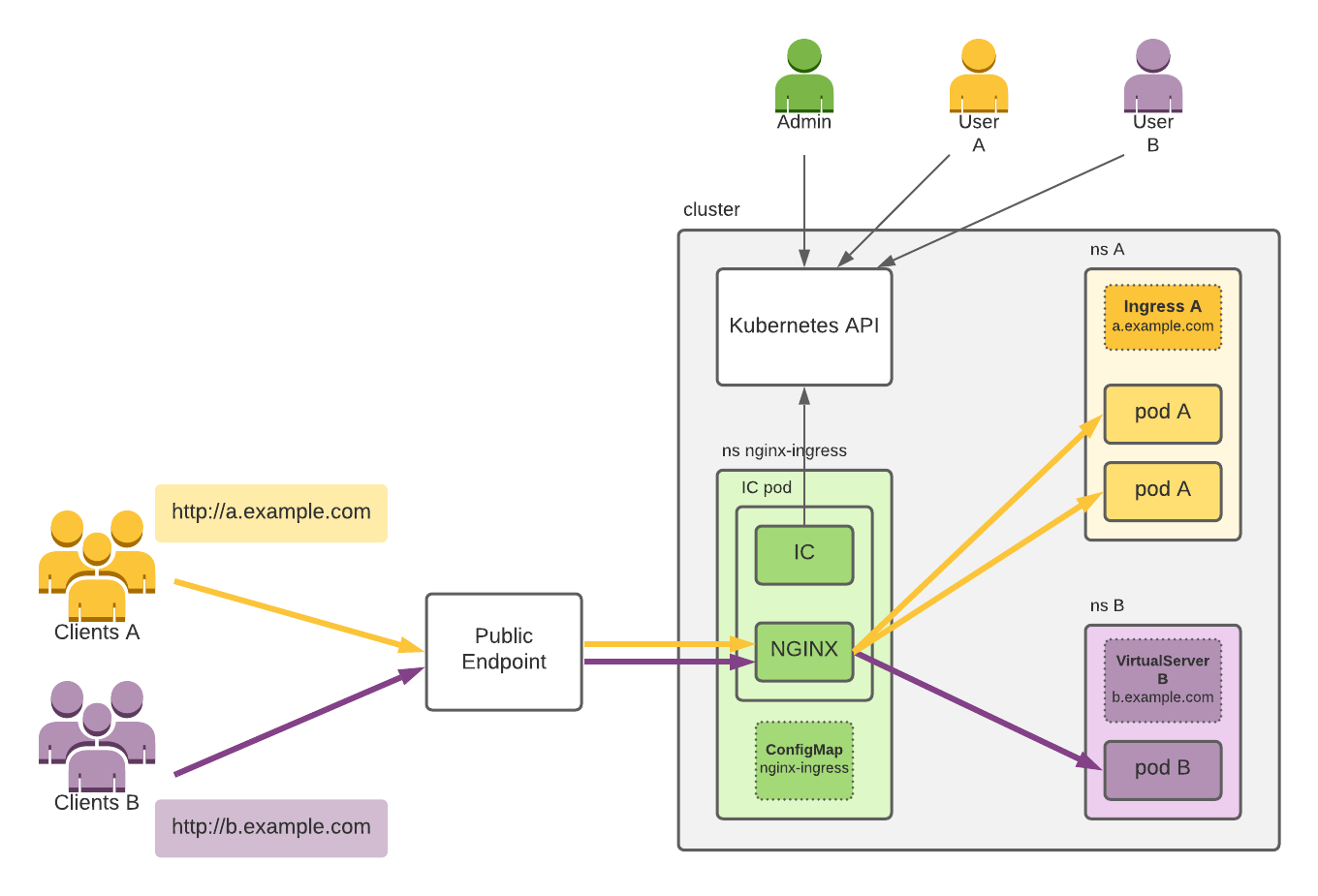

I’ve used the term proxy to generally refer to ingress controllers, external load balancers, and operators that subscribe to the Kubernetes API server and watch for changes to Kubernetes services2. In this post I’ll use a few examples of proxies that I know pretty well:

- Two ingress controllers

- Community ingress controller: an ingress controller developed and maintained by the community

- NGINX Ingress Controller: an ingress controller developed by NGINX developers

- F5 Distributed Cloud (XC) Customer Edge(CE): can act as external load balancer 3

- F5 Container Ingress Services (CIS): an operator that updates a BIG-IP device outside the cluster

Ingress Controllers

Firstly, there’s two ingress controllers which are often confused because they have similar names.

- The community ingress controller is developed by the community, hosted at kubernetes/ingress-nginx, with docs on kubernetes.io. It is based on NGINX Open Source, but the company NGINX doesn’t control it (although there is a commitment from F5 NGINX to support that project).

- The NGINX version is found at nginxinc/kubernetes-ingress, developed and maintained by F5 NGINX with docs on docs.nginx.com. Because NGINX is the custodian of this open source project, they control the development philosophy of production readiness, backward compatibility, security, no third party modules, and enterprise support.

Because an ingress controller is a pod itself and is watching the Kubernetes API closely and reconfiguring itself immediately, the time lapse between an endpoint being removed and the proxy configuration being updated is very short.

Real world ingress controller use cases

If you search the web, you’ll find folks that implemented the PreStop hook to overcome instances where an ingress controller had a stale config because backend apps started shutting down at the same time as they were removed from endpoints.

I spoke to a Product Manager from NGINX about the PreStop hook and he told me that he’s never heard about anyone needing to do this for NGINX’s own ingress controller (however, he could not speak for the community version or other ingress controllers). NGINX’s ingress controller dynamically updates it’s own configuration so quickly that it’s almost not possible for terminating pods to exist as upstream pool members in NGINX.

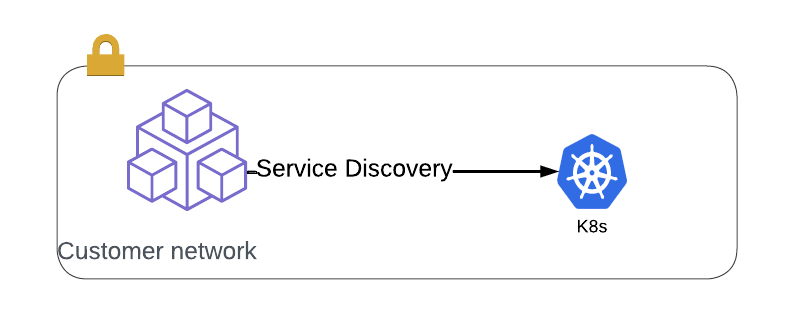

External load balancer

An F5 XC CE device can use a Service Account to authenticate to the Kubernetes API server from outside of the cluster. I’ve written about this before. In this setup, the CE can configure itself to load balance incoming requests directly to pod IP addresses within a cluster. Users can send requests to this device (or any device on the mesh from which the site is advertised) and their request will be proxied directly to a pod’s IP address.

Depending on the latency of API calls from external LB to cluster API server, there may be a slightly longer time lapse between a pod’s termination and the load balancer learning about this.

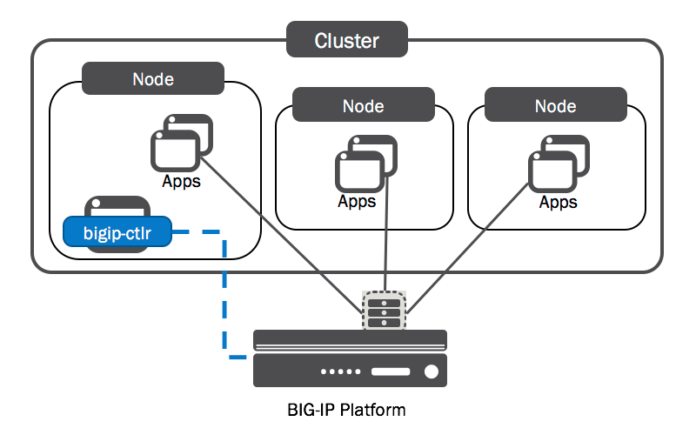

Operator and external load balancer

F5 CIS is an enterprise-level operator and a good example of real-world complexities faced by large companies. CIS runs as a container within a cluster and subscribes to the Kubernetes API, just like other clients. However, unlike an ingress controller that configures itself, upon learning of changes to endpoints CIS will send an API call to an F5 BIG-IP device that is outside of the cluster.

The API calls pictured in blue are made very quickly after CIS learns of changes to endpoints, but the time for BIG-IP to apply the configuration required can be a few seconds. It’s also possible to batch these API calls with the --as3-post-delay argument, which will increase the delay between changes to endpoints and proxy updates.

Important! This is the scenario that is most likely to require a PreStop hook. Since the BIG-IP must receive API calls from an operator, but mostly because large configuration updates may take a few seconds, this is the architecture most vulnerable to the asynchronous nature of Kubernetes endpoint updates.

Why do we need to make shutdowns more graceful?

The main reason is because of how rolling updates work, which is the default strategy for deployment updates.

When a deployment manifest is updated and applied, a rolling update forces each pod’s termination and replacement with an updated pod. This happens in a rolling fashion, by default to 25% of pods at a given time (controlled by the maxUnavailable setting).

How is a pod terminated during rolling updates?

Firstly the Kubernetes management plane will remove the existing pod from the Endpoints object. At the same time the kubelet will issue a SIGTERM to the pod which will shutdown the pod application. If the process is still running after 30 seconds4, the kubelet will force kill the process with a SIGKILL.

Because the pods begin shutting down at the same time as removal from the Endpoints object, there is no time alloted for components like ingress controllers or external load balancers to update their own configuration before their target pods are shutting down.

This is why there can be a small window of time when the proxy’s targets are not synchronized with the true state of running pods in a service. Usually this window is very short, but it can be longer for external load balancers. In either case, if a request arrives at an ingress controller or external load balancer during this window, it may be routed to a pod that is being terminated, or no longer exists, resulting in a failed request.

This is the order of operations for pod shutdown:

| Order | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | Pod is removed from Endpoints object |

| 1 | Pod is sent SIGTERM signal |

| 1 | terminationGracePeriodSeconds grace period begins |

| 2 | Clients watching the K8s api server learn about removal from Endpoints |

| ! | This is the time window when requests can be sent to terminating pods |

| 3 | Ingress controllers and external load balancers update their configuration |

| 4 | SIGKILL is sent (if Pod process is not already shut down) |

How can we design more graceful shutdowns?

There are a few settings within Kubernetes that we can configure to allow more time for ingress controllers and external load balancers to configure themselves: health probes, PreStop hooks and the terminationGracePeriodSeconds setting. Additionally, health monitors from your ingress controller or load balancer can compliment those configured within Kubernetes.

An order of operations like this might look better:

| Order | Action |

|---|---|

| 1 | Pod is removed from Endpoints object |

| 1 | PreStop hook is run |

| 1 | terminationGracePeriodSeconds grace period begins. We can increase this |

| 2 | Clients watching the K8s api server learn about removal from Endpoints |

| 3 | Ingress controllers and external load balancers update their configuration |

| 4 | Pod is sent SIGTERM signal (when PreStop hook is complete) |

| 5 | SIGKILL is sent (if Pod process is not already shut down) |

Startup, Liveness, and Readiness Probes

As discussed above, the three types of probes are essential Kubernetes knowledge. If these probes are not configured, traffic may reach your pods before or after they are healthy and ready to receive requests. You should be aware of how each of the detailed settings in the probes works with your application, and what happens if they are left unconfigured.

PreStop hooks

A PreStop hook can run a command, send a HTTP request, or Sleep (pause) a container before the SIGTERM from the kubelet shuts down the application. In practice, this means we have a mechanism to gracefully delay application shutdown when pods are being terminated in a rolling update. The hook is also called when termination is due to liveness/startup probe failure (another good reason to use readiness probes).

This graceful delay should be configured to allow enough time for ingress controllers or external load balancers to update their configurations. Documentation also reminds us5:

If the PreStop hook needs longer to complete than the default grace period allows, you must modify terminationGracePeriodSeconds to suit this.

terminationGracePeriodSeconds

TerminationGracePeriodSeconds is a pod-level lifecycle setting6. The default grace period is 30 seconds, and this acts like a timeout, beginning at the same time as the PreStop hook (or SIGTERM if there is no PreStop hook). So if your intention with the PreStop hook is to delay pod deletion by more than 30 seconds, you should increase this also.

Health checks from your load balancer or ingress controller

BIG-IP, XC, and NGINX all have enterprise-level health checks which can monitor apps via pod IP addresses. This can guard against scenarios where startup, liveness, or readiness probes are not configured.

Conclusion

PreStop hooks, terminationGracePeriodSeconds, and readiness probes are all Kubernetes settings that can allow us to improve avaialability of an application within Kubernetes, all without touching the application code running in containers.

Many of the same rules apply for configuration of Kubernetes as in traditional environments. By understanding the nature of your application and it’s delivery (networking, security, application startup, upgrades, automated deployments, etc), you can improve the user experience and make application management more robust. Thanks for reading!

Related articles

- Graceful shutdown and zero downtime deployments in Kubernetes. This article is an excellent resource that covers the sequence of events very nicely. Much of my own article is a repeat of this overview, but I focus on examples of ingress controllers, load balancers, and operators a little more.

- Kubernetes best practices: terminating with grace. This nice summary of events is a clear overview of the pod termination lifecycle.

- Graceful Shutdown with Lifecycle preStop Hook. Another good article on best practices with PreStop hooks.

- Pod Lifecycle documentation.

- pod-graceful-drain - here’s another clever hack: intercept pod deletion API calls and isolate a pod instead of terminating it. This is for further reading if interested.

-

This is true for services of type ClusterIP and LoadBalancer, where the load balancer is aware of individual pod IP addresses. This is not true for services of type NodePort, where the load balancer will direct traffic only to node IP addresses. ↩

-

There are also other components within Kubernetes that do not proxy traffic, but must subscribe to changes to endpoints. For example, CoreDNS must keep track of IP addresses for headless services, and the Cloud Controller Manager will need to know pod IP addresses in order to update cloud load balancers. ↩

-

The F5 Distributed Cloud Customer Edge device can act as an external LB for existing Kubernetes clusters, but it can also be deployed within Kubernetes as an applicatin itself, or even run it’s own Kubernetes cluster. In this case, I’m using it as an example of a third party external load balancer to Kubernetes. ↩

-

30 seconds by default. Configurable with terminationGracePeriodSeconds. ↩

-

Documentation also tells us that ‘If the preStop hook is still running after the grace period expires, the kubelet requests a small, one-off grace period extension of 2 seconds.’ ↩

-

Since Kubernetes 1.25 it can also be set at a probe level ↩